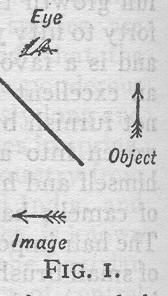

Fig. 1.

This is a reprint of

Joley, Charles Jasper "Camera Lucida." in Encyclopædia Britannica. Eleventh Edition. ("Handy Volume Issue") NY: Encyclopædia Britannica Company, 1910. Vol. V, p. 104.

The notes on the contributors describe Charles Jasper Joley, F.R.S., F.R.A.S. (1864-1906) as:

Royal Astronomer of Ireland and Andrews Professor of Astronomy in the University of Dublin 1897-1906. Fellow of Trinity College, Dublin. Secretary of the Roayal Irish Academy. (vi)

I would guess that Joley is the same person referred to as "Prof. J. Joly [sic] of Dublin," inventor of a colo[u]r photographic process, in the article "Photography" by Abney et. al. also reprinted in this Library of Antiquarian Technology.

The transcription here preserves the line breaks of the original, which probably isn't necessary.

CAMERA LUCIDA,

an optical instrument invented by Dr.

William Hyde Wollaston for drawing in perspective. Closing

one eye and looking vertically downwards with the other through

a slip of plain glass, e.g. a microscope cover-glass, held close to

the eye and inclined at an angle of 45° to the horizon, one can

see the images of objects in front, formed by reflection from the

[column 2 begins here]

surface of the glass, and at the same time one can also see through

the transparent glass. The virtual images of the objects appear

projected on the surface of a sheet of paper placed beneath the

slip of glass, and their outline can be accurately traced with a

pencil. This is the simplest form of the camera lucida. The

image {see fig. 1) is, however, inverted and

[fig. 1 appears inset to the right here]

perverted, and it Is not very bright owing to

the poor reflecting power of unsllvered glass.

The brightness of the image is sometimes in-

creased by silvering the glass; and on removing

a small portion of the silver the observer can

see the image with part of the pupil while he

sees the paper through the unsilvered aperture

with the remaining part. This form of the in-

strument is often used in conjunction with the

microscope, the mirror being attached to the eye-piece and the

tube of the microscope being placed horizontally.

Fig. 1.

[The representation of the eye in the upper left of this figure is a little hard to make out. I believe that it is a drawing of an eye, looking downward, with the eyebrow to the left. Here it is at a higher resolution:

[Fig. 1., Detail of Eye]

[Fig. 1., Detail of Eye, Rotated] ]

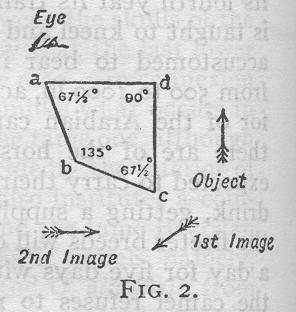

About the beginning of the 19th century Dr Wollaston in-

vented a simple form of the camera lucida which gives bright

and erect images. A four-sided prism of glass is constructed

having one angle of 90°, the opposite angle of 135°, and the two

remaining angles each of 67 1/2°. This is represented in cross-

section and in position in fig. 2. When the pupil of the eye is

[fig. 2 appears inset to the right here]

held half over the edge of the prism a,

one sees the image of the object with with

one half of the pupil and the paper with

the other half. The image is formed by

successive total reflection at the surfaces

b c and a b. In the first place an in-

verted image (first image) is formed in

the face b c, and then an image of this

image is formed in a b, and it is the

outline of this second image see pro-

jected on the paper that is traced by the

pencil. It is desirable for two reasons that the image should

lie in the plane of the paper, and this can be secured by placing

a suitable lens between the object and the prism, If the image

does not lie in the plane of the paper, it is impossible to see it

and the pencil-point clearly at the same time. Moreover, any

slight movement of the head will cause the image to appear to

move relatively to the paper, and will render it difficult to obtain

an accurate drawing.

Fig. 2.

Before the application of photography, the camera lucida was

of considerable importance to draughtsmen. The advantages

claimed for it were its cheapness, smallness and portability;

that there was no appreciable distortion, and that its field was

much larger than that of the camera obscura. It was used largely

for copying, for reducing or,for enlarging existing drawings. It

will readily be understood, for example; that a copy will be half-

size if the distance of the object from the instrument is double

the distance of the instrument from the copy. (C. J. J.)

This article by Joley is in the public domain.

The reprint of it here is dedicated to the

Public Domain.

Important disclaimers of warranty

and liability in the presentation of public domain material.

The rest of this page is copyright © 2003-2004 by David M. MacMillan.

This work is licensed under a

Creative Commons License,

which includes important disclaimers of warranty and liability.

lemur.com is a service mark of

David M. MacMillan

and Rollande Krandall.

Other trademark

recognition.

Presented originally by lemur.com.SM