Fig. 2.

CAMERA OBSCURA

105

camera obscura, which was extensively used in sketching from

nature, before the introduction of photography, although it is

now scarcely to be, seen except as an interesting side-show at

places of popular resort. The image formed on the paper may

be traced out by a pencil, and it will be noticed that in this case

the image is real - not virtual as in the case of the camera

lucida. Generally the mirror and lens are combined into a

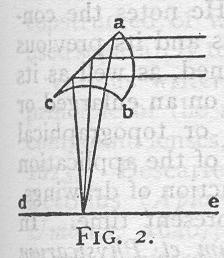

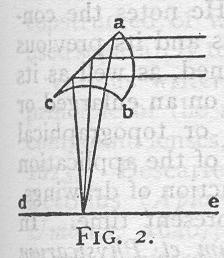

single piece of worked glass represented in section in fig. 2.

[Fig. 2 appears here inset on the left]

Rays from external objects are first re-

fracted at the convex surface a b, theu totally

reflected at the plane surface a c, and finally

refracted at the concave surface b c (fig. 2)

So as to form an image on the sheet of paper

d e. The curved surfaces take the place of

the lens in fig. 1, and the plane surface per-

forms the function of the mirror. The prism

a b c is fixed at the top of a small tent fur-

nished with opaque curtains so as to prevent the diffused day-

light from overpowering the image on the paper, and in the

darkened tent the images of external objects are seen very

distinctly.

Quite recently, the camera ohscura has come into use with

submarine vessels, the periscqpe being simply a camera obscura

under a new name. (C.J.J)

Fig. 2.

History. -

The invention of this instrument has generally been

ascnbed, as in the nInth edition of this work, to the famous

Neapolitan savant of the 16th century, Giovanni Battista della

Porta, but as a matter of fact the principle of the simple camera

obscura, or darkened chamber with a small aperture in a window

or shutter, was well known and in practical use for observing

eclipses long before his time. He was anticipated in the improve-

ments he claimed to have made in it, and all he seems really to

have done was to popularize it. The increasing importance

of the camera obscura as a photographic instrument makes it

desirable to bring together what is known of its early history,

which is far more extensive than is usually recognized. In

southern climes, where during the summer heat it is usual to

close the rooms from the glare of the sunshine outside, we may

often see depicted on the walls vivid inverted images of outside

objects formed by the light reflected from them passing through

chinks or small apertures in doors or window shutters. From

the opening passage of Euclid's Optics (c. 300 B.C.), which

formed the foundation for some of the earlier middle age treatises

on geometrical perspective, it would appear that the above

phenomena of the simple darkened room were used by him to

demonstrate the rectilinear propagation of light by the passage

of sunbeams or the projection of the images of objects through

small openings in windows, &c. In the book known as Aris-

totle's Problems (sect. xv. cap. 5)

we find the correlated problem

of the image of the sun passing through a quadrilateral aperture

always appearing round, and he further notes the lunated image

of the eclipsed sun projected in the same way through the

interstices of foliage or lattice-work.

There are, however, very few allusions to these phenomena

in the later classical Greek and Roman writers, and we find the

first scientific investigation of them in the great optical treatise

of the Arabian philosopher Alhazen (q.v.), who died at Cairo in

A.D. 1038. He seems to have been well acquainted with the

projection of images of objectsth through small apertures, and to

have been the first to show that the arrival of the image of an

object at the concave surface of the common nerve - or the

retina - corresponds with the passage of light from an object

through an aperture in a darkened place, from which it falls

upon a surface facing the aperture. He also had some knowledge

of the properties of concave and convex lonses and mirrors in as

formimg images. Some two hundred years later, between

A.D. 1266 and 1279, these problems were taken up by three

almost contemporaneous writers on optics, two of whom, Roger

Bacon and John Peckham, were Englishmen, and Vitello or

Witelo, a Pole.

That Roger Bacon was acquainted with the principle of the

camera obscura is shown by his attempt at solving Aristotle's

[column 2 starts here]

problem stated above, in the treatise De Speculis,

and also from

his references to Alhazen's experiments of the same kind, but

although Dr John Freind,in his History of Physick,

has given him

the credit of the invention on the strength of a passage in the

Perspective, there is nothing to show that he construceed any

instrument of the kind. His arrangement of concave and plane

mirrors, by which the realistic images of objects inside the house

oz in the street could be rendered visible though intangihle,

there alluded to, may apply to a camera on Cardan's principle or

to a method of aerial projection by means of concave mirrors,

which Bacon was quite familiar with, and indeed was known

long before his time. On the stregth of similar arrangements of

lenses and mirrors the invention of the camera obscura has also

been claimed for Leonard Digges, the author of Pantometria

(1571), who is said to hilve constructed a telescope from informa-

tion given in a book of Bacon's experiments.

Archbishop Peckham, or Pisanus, in his Perspectiva Communis

(1279), and Vitello, in his Optics (1270), also attempted the

solution of Aristotle's problem, but unsuccessfully. Vitello's

work is to a very great extent based upon Alhazen and some of

the earlier writers, and was first published in 1535. A later

edition was published, together with a translation of Alhazen,

by F. Risner in 1572.

The first practical step towards the development of the camera

obscura seems to have been made by the famous painter and

architect, Leon Battista Alberti, in 1437, contempoaneously

with the invention of printing. It is not clear, however, whether

his invention was a camera obscura or a show box, but in a

fragment of an anonymous biography of, him, published in

Muratori's Rerum Itaicarum Scriptores (xxv. 296), quoted by

Vasari, it is stated that he produced wonderfully painted

pictures, which were exhibited by him in some sort of small

closed box through a very small aperture, with great verisimili-

tude. These demonstrations were of two kinds, one nocturnal,

showing the moon and bright stars, the other diurnal, for day

scenes. This description seems to refer to an arrangement of a

transparent painting illuminated either from the back or the front

and the image projected through a hole onto a white screen in a

darkened room, as described by Porta (Mag. Nat. xvii. cap. 7)

and figured by A. Kircher (Ars Magna Lucis et Umbrae), who

notes elsewhere that Porta had taken some arrangement of pro-

jecting images from an Albertus; whom he distinguished from

Albertus Magnus, and who was probably L.B. Alberti, to whom

Porta also refers, but not in this connexion.

G. B. I. T. Libri-Carucci dalla Sommaja (1803-1869), in his

account of the invention of the camera obscura in Italy (Histoire

des sciences mathématiques en Italie, iv. 303),

makes no mention

of Alberti, but draws attention to an unpublished MS. of Leonardo

da Vinci, which was first noticed by Venturi in 1797, and has

since becn published in facsimile in vol. ii. of J. G. F. Ravaisson-

Mollien's rcproductions of thc MSS. in the Institut de France at

Paris (MS, D, fol. 8 recto).

After discussing the structure of the

eye he gives an experiment in which the appearance of the

reversed images of outside objects on a piece of paper held in

front of a small hole in a darkened room, with their forms and

colours, is quite clearly described and explained with a diagram,

as an illustration of the phenomena of vision. Another similar

passage is quoted by Richter from folio 404b of the reproduc-

tion of the Codice Atlantico, in Milan,

published by the Italian

government. These are probably the earliest distinct accounts

of the natural phenomena of the camera obscura, but remained

unpublished for some three centuries. Leonardo also discussed

the old Aristotelian problem of the rotundity of the sun's image

after passing through an angular aperture, but not so successfully

as Maurolycus. He has also given methods of measuring the

sun's distance by means of images thrown on screens through

small apertures. He was well acquainted with the use of magni-

fying glasses and suggested a kind of telescope for viewing the

moon, but does not seem to have thought of applying a lens to

the camera.

The first published account of the simple camera obscura was

discovered by Libri in a translation of the Architecture of

This article by Joley and Waterhouse is in the public domain.

The reprint of it here is dedicated to the

Public Domain.

Important disclaimers of warranty

and liability in the presentation of public domain material.

The rest of this page is copyright © 2003-2004 by David M. MacMillan.

This work is licensed under a

Creative Commons License,

which includes important disclaimers of warranty and liability.

lemur.com is a service mark of

David M. MacMillan

and Rollande Krandall.

Other trademark

recognition.

Presented originally by lemur.com.SM