Caution: I rushed this Notebook out the door because the basic information in it, that Jaugeon's text and plates are freely available, is so very important. But I'm quite sure that I've introduced errors in doing so (to the extent that there may be simple errors of grammar and construction). I regret that these may complicate the already difficult multi-century history of publication of this work and I would appreciate corrections.

This is a part of the Notebook of General Literature on Making Printing Matrices and Types . It is also cited in the Survey of the Literature on Typographical Punchcutting in Steel by Hand.

This work is at the same time one of the most important documents in our present knowledge of the history of type-making technology and one of the most frustrating. Briefly, Jaugeon's 1704 manuscript and the eight plates engraved to accompany it (which in turn were a part of a much larger undertaking with many more plates and a much longer text) constitute a comprehensive treatise on all aspects of punchcutting, matrix making, mold making, and hand casting, Researched and written at the close of the 17th century and the first years of the 18th (1693 - 1704), it is our second-oldest comprehensive work on the subject. 1 Its creation was intertwined with an important event in the history of type: the creation of the Romain du Roi, which Mosley has identified as "the first example of a type design, in which the form of the letter can be seen to have been conceived independently of the artisan who would fix it in metal." ( {Mosley 1991}, p. 63.) Yet this work was not published, and even today no proper edition has appeared in any language.

The good news for the 21st century reader is that portions and versions of it are now available, some on paper and some online. Although it remains a difficult source it is no longer an impossible one (as it was through even the late 20th century).

Note: Although several people contributed to this lathe 17the century work, as a shorthand I will use the name of the primary author of the text, Jaugeon, to refer to the work as a whole in any form.

Given the obscure and confusing publication history (or non-publication history) of this work, the best thing to do is to identify each stage in turn. This account may be hard to understand with this much detail. Take comfort in the fact that it is impossible to understand with any less detail.

The intellectual scene for this work was set in the 1660s by two actions of Jean-Baptiste Colbert, the Minister of Finance for Louis XIV of France. One of these was his suggestion of the creation of the Académie Royale des Sciences itself (which is now an academy within the Institut de France, and which still possesses the original manuscript of this work). The other was his less tightly focused publication project to create in print a (metaphorical) "Cabinet du Roi" to catalogue and illustrate the collections and works of the King (who, famously, declared himself to be the French state as well).

The exact definition of what the "Cabinet du Roi" was is a matter of some interpretation. So far as I can tell, it is usually thought of as a loose collection of about two dozen books, not necessarily published uniformly. But Jammes argues for a much closer connection to the royal collections at Versailles. See {Jammes 1965}, pp. 80-81. Its "crowning glory" {Jammes 1965}, p. 81. was a volume devoted to a series of medals commemorating the successes of the reign of Louis XIV for which a new type, now known as the Romain du Roi, was created.

No part of Jaugeon text or its accompanying plates is a part of the Cabinet du Roi (Colbert died in 1683, while the committee with which Jaugeon served was not convened until 1693), but Colbert's projects established a framework whereby it was natural for the French state to interest itself in all aspects of science and industry and to document them comprehensively. (Less formally, and sometimes in opposition to the state, the Encyclopédie of Diderot and d'Alambert owes something to the same mindset.)

For more on the Cabinet du Roi, see Sauvy's chapter "Le Cabinet du Roi et les projets encyclopédiques de Colbert" in L'Art du Livre à l'Imprimerie Nationale {Sauvy 1973}.

For more on the relationship between Colbert, the Académie Royale, and the Romain du Roi, see {Jammes 1965}.

2. The Académie Royale and the Descriptions des Arts et Métiers

From relatively early points in its existence, it was suggested to the Académie that it undertake to research and publish a large collection of works devoted to the manufacturing arts. Jammes dates the first such suggestion to 1666 and the "official" commencement of the project to a report read to the Académie in 1675 by Charles Perrault, its secretary, at the request of Colbert. It "enjoined the academicians to describe 'all the techniques used in the practice of the arts.'" ( {Jammes 1965}, pp. 71-72. (Jammes writes here in English and cites L'Art du Livre {IN 1951} as his source. But I cannot seem to find anything about Perrault's report, or the original French wording of this quotation, in that catalogue. Of course, I can't read French, so my comprehension of these texts is quite limited. But Mosley (whose knowledge is anything but limited!) identifies it in the minutes of the Académie on 19 June 1675. {Mosley 2016}, p. 7._

This was the official beginning, insofar as it was the point at which the Académie became formally aware that it was the will of the State that they should do this. But, Jammes notes, "It appears that this enterprise met with a somewhat cool response" in 1675. This is an understatement, as work did not commence until 1693, and then only by a relatively small committee.

That committee (or "commission") was headed and initially hosted by the Abbé Jean-Paul Bignon. They began with the study of type, but this was intended only to be the first of a comprehensive series of books covering all fields of industry, the Descriptions des Arts et Métiers, faites ou approuvées par messieurs de l'Académie Royale des Sciences ("Descriptions of the Arts and Trades, made or approved by gentlemen of the Royal Academy of Sciences"). This series had a long and difficult history. It was "ordered" (as noted above) in 1675, but not begun in earnest until 1693. Nothing was actually published until 1761 (68 years later), and publication continued until 1788 (not long before the termination of all "royal" activities in France).

Those volumes of the Descriptions written by André Jacob Roubo and published between 1769 and 1774 as L'Art du Menuisier ("The Art of the Joiner") have become a sacred text in traditional woodworking circles. For a modern translation of this and an extraordinary reprint of its plates, see Lost Art Press.

The first point to make about the Descriptions des Arts et Métiers (at least for those who are unfamiliar with it) is that it was a project completely independent of the much better known Encyclopédie edited by Diderot and d'Alambert and published between 1751 and 1772. Indeed there seems to have been some friction between the two projects, particularly as the plates of the Encyclopédie, though begun long after the Descriptions, adopted its format.

The second point to make is that, ironically, the comprehensive study made by the Bignon Commission on type and typefounding was never published as a part of the Descriptions (or, indeed, ever published at all).

Beyond this, the history of the Descriptions, and the work of others in writing and publishing its volumes, becomes a subject in its own right. The typographical work of interest here was complete, though unpublished, by 1704 (Jaugeon's manuscript). The Romain du Roi was introduced in 1702 in the book Medailles sur les principaux evenements du regne de Louis le Grand. Philippe Grandjean, who cut the punches for the Romain du Roi based on the designs of the Bignon Committee, died in 1714; the last of the plates showing these designs was not completed until 1718 ( {Jammes 1965}, p. 76). Indeed, the Romain du Roi as a typeface family was never published (it was, after all, a house face). Jammes notes that "During the eighteenth century only a few prints were taken..., but experts came to know of [these plates]." (p. 76)

For the Descriptions generally, see:

{Cole & Watts 1951} Cole, Arthur Harrison and George B. Watts. The Handicrafts of France as Recorded in the Descriptions des Arts et Métiers 1761-1788. Boston: Baker Library of the Harvard Graduate School of Business Administration, 1951.

Originally Publication No. 8 of the Kress Library of Business and Economics. This is now available as a print-on-demand reprint by Literary Licensing LLC (2011-10-15), ISBN-13: 978-1258208363.

For references to the primary sources of information on the formation of the Bignon committee (many of which were overlooked until the 1960s) and its work (primarily with reference to the Romain du Roi), see {Jammes 1965}.

See also L'Art du Livre {IN 1951} , (in particular p. 13 and also the section "Les 'Types du Roi'", p. 82, the introduction to which outlines the work of the committee) and Jammes' "Le Grandjean" in L'Art du Livre {IN 1973} .

Many volumes of the Descriptions have been digitized, but many have not. A distinction should also be made between the original volumes published in Paris and a more uniform edition, under the same title, which was published in Neuchatel from 1771 to 1798. The volumes of the Neuchatel edition have been digitized by the Conservatoire Nationale des Arts et Métiers (CNAM) in their cleverly named CNUM (Bibliothèque numérique en histoire des sciences et des techniques): http://cnum.cnam.fr

The committee gathered by Bignon studied much beyond type, but they started with typefounding and with the design of the Romain du Roi. There were three members (besides Bignon), all with either experience in or appreciation of practical mechanics: Jacques Jaugeon (1655 - ?), Jean Truchet (1657 - ?) who became Père Sébastian Truchet upon becoming a Carmelite monk, and Gilles Filleau des Billettes (1634 - ?). ( {Jammes 1965}, p. 72 and Mosley 1991, p. 62). None of them, however, had any previous knowledge of type.

Mosley indicates that it was probably Filleau des Billettes who "was responsible for [the] general plan and ... method of working" of the Descriptions (p. 62). All of them, however, seem to have taken an interest in typefounding and the Romain du Roi. Mosley reproduces three preliminary drawings of hand molds and type dressing equipment from Truche's papers, noting that they may be by Truchet's own hand Mosley 1991, two plates following p. 64). Plates were commissioned from at least two engravers, ouis Simonneau (1654 - 1727) and the otherwise unknown G. Quineau. Jaugeon was the one who finally wrote up the typefounding material, in a manuscript finished in 1704.

There doesn't seem to be any firm reason given in the literature as to why the work on typefounding was not included in the Descriptions. I would think that there are two possibilities, both colored by the fact that no volume of the Descriptions appeared until 57 years after Jaugeon completed his manuscript. First, the primary task of the Committee, in the eyes of the outside world, was not the technology of typefounding but the design of the Romain du Roi. This had, in the intervening years, come in for serious criticism. In particular, Fournier speaks harshly of it and says that it implies that its authors were ignorant of the practices of making real type. Second, Jaugeon's prose gained a reputation for unreadability. Mosley says of it "To read Jaugeon's leaden and prolix text can be a depressing experience" Mosley 1991, p. 64). Jammes also notes that Jaugeon's papers were not well received by the Académie ( {Jammes 1965}, pp. 73-74, citing the unpublished version of the official minutes of the Académie).

The two basic references in English on Bignon's committee are {Jammes 1965} and James Mosley's 1991 article in Matrix 11 {Mosley 1991} . They aren't cheap, but they're worth having in every serious typefounder's library. (Acquiring them cost me over $400: half for the price of one number of Matrix and half because I had to purchase a 20 number run of the Journal of the PHS to get a single article. The cost of basic reference materials is a serious problem for the aspiring typefounders who must carry this craft into the future, and as such is a threat to type itself.)

In his 2015 translation of the portion of Jaugeon on hand molds, Mosley says that {Jammes 1961} "remains the fundamental study":

See also Jammes' "Le Grandjean" in L'Art du Livre {Jammes 1973}.

4. The Manuscript (Jaugeon) and Plates (Simonneau, Quineau)

Only the first eight of these plates are of direct interest to the practical typefounder. To these the modern reader may add the three drawings from Truchet's papers and one wash drawing, all reproduced in {Mosley 1991}.

Jaugeon's original manuscript survives in one copy only. It has never been reproduced in print. It has been microfilmed. Both {Jammes 1965} (p. 72 n5) and {Mosley 2015} (p. 8) identify it as MS 2741 in the libary of the Institut de France.

Jaugeon [, Jacques]. Description et perfection des Arts-et-Métiers, Tome I. Des arts de construire les caractères, de graver les poinçons de lettres, de fondre les lettres, d'imprimer les lettres et de relier les livres. Manuscrits de l'Institut de France. Shelfmark: MS 2741. Date: 1704. Physical description: Papier. 274 feuillets. Plume et crayon. 410 × 290 mm. Reliure veau [calf].

Mosley describes it as "a small folio ... with the ownership stamp of the library of the Académie royale des Sciences on the title-page." It has an online catalog citation here: http://www.calames.abes.fr/pub/#details?id=IF2C12510 This citation also notes: "Les chercheurs souhaitant être admis comme lecteurs doivent être présentés au directeur de la bibliothèque par deux membres de l'Institut" ("Researchers wishing to be admitted as readers must be presented to the director of the library by two members of the Institue." So much for everything in the world being online!)

{Jammes 1965} observes that two other manuscripts in the library of the Institut de France, MS. 1064 and 1065, "contain a number of important drawings and engraved plates which partly complete MS. 2741" (p. 72). He doesn't say which plates and drawings, though.

The online catalogue entry for these manuscripts, at: http://www.calames.abes.fr/pub/#details?id=IF2B10994 supplies further details:

Planches des "Descriptions des Arts et Métiers, faites ou approuvées par MM. de l'Academie Royale des Sciences." Shelfmark: Ms 1064-1065 bis Réserve. Physical description : Papier. 122, 110, 240 et 70 planches. Dessins à la plume, gravures. 570 × 410 mm. Reliure veau (1er et 2e volumes), papier (3e volume).

In other words, its a collection of plates from the Descriptions, some of which may be relevant.

This is a later manuscript copy of Jaugeon, made "in about 1780". {Jammes 1965} (p. 72 n5) and {Mosley 2015} (p. 8) identify it as MS 9157 and 9158 in the Cabinet des Manuscrits of the BNF.

Bibliographic information from the BNF/Gallica:

Description et perfection des arts et métiers, des arts de construire les caractères, de graver les poinçons de lettres, de fondre les lettres, d'imprimer les lettres et de relier les livres, par monsieur JAUGEON, de l'Accadémie roale [sic, for royale] des Sciences. Shelfmark: Français 9157. Date d'édition: 1701-1800 [Mosley says "about 1780"]

Jammes says that its text is "less complete" but that it "contains plates which are not in the first manuscript" (p. 72). Mosley says it "introduces some errors, but it appears to be intended as a full transcription of the original text, repeating its mistakes" (p. 8).

It is an extraordinarily important document, however, for the simple reason that it is available for free online from the "Gallica" digital library of the Bibliothèque Nationale de France. This digital edition, first made available in 2012 (Ms. Fr. 9158) and 2013 (Ms. Fr. 9157) represents the publication of Jaugeon, some 312 years after its writing. It is also the first time that the very important plates have been available outside of expensive fine press editions.

(Since I'm doing this chronologically, see the section on the Digital Availability of the Second MS (2012, 2013), below for access information, local copies, and convenient extracts of the plates.)

The second manuscript was also displayed in the 1951 Imprimerie Nationale exhibition at the Galerie Mazarin. It is cited in the catalogue of that exhibition, L'Art du Livre {IN 1951} , as item 166, pp. 83-84. Interestingly, the citation covers not just two manuscipt volumes (Français 9157, 9158) but twelve: Français 9153 - 9164. The Catalogue reproduces one page from them, showing the italic of the Romain du Roi for letters 'A' through 'F'. This page is from MS Fr. 9157, where it bears the page number 386. It is image 470 in the digitization of this manuscript in Gallica (see below).

5. 18th - Mid-20th Century Availability of the Plates

Jaugeon's text was available only in manuscript until 2012. The plates fared slightly better - but only a little.

In a footnote (n. 23) to his 1991 publication of these plates, James Mosley gives the basic titles under which "collections of proofs" of these plates circulated in the 18th century {Mosley 1991}. It would appear that these were relatively large collections of plates for various trades, not just the few plates devoted to typefounding and printing. Once you have these titles, you'll find that they show up often enough in 19th century bibliographic guides and handbooks on creating a well-stocked library. (Of course these are quite frustrating, as they are simply bibliographic citations - not the plates themselves.) In one such handbook, Thomas Hartwell Horne makes this illuminating remark about them:

"Simmoneau. - Recueil d'Estampes gravées en taille-douce par Louis Simonneau, pour servier à l'histoire de l'art de l'imprimerie et de la gravure. 1694, folio.

"Simonneau. - Recueil d'Estampes, pour servier à l'histoire des arts et métiers, gravées en taille-douce , depuis 1694 jusqu'à 1710, folio.

"'Both these collections,' says Peignot, 'are scarce and curious, for the beauty of their execution as well as the small number struck off. They were executed, by order of Louis XIV., under the direction of Louis Simonneau, by the most able artists. The completest copy of these collections, it is believed, should consist of 168 plates. They were never intended for sale." ( {Horne 1814}, p. 501)

(But note that this 18th/19th century attribution of all of these plates to Simonneau is not correct; see {Mosley 1991} for details.)

{Horne 1814} Horne, Thomas Hartwell Horne. An Introduction to the Study of Bibliography, Vol. II London: T. Cadwell and W. Davies, 1814.

6. Late 20th Century Publication of the Plates

As you may have noticed, we owe a tremendous debt to André Jammes and James Mosley for our present knowledge of these plates. (But the text itself remained completely unavailable, outside of a trip to Paris, until the 21st century.)

{Jammes 1973} Jammes, André. "Le Grandjean et la naissance de la typographie moderne." [a chapter in] L'Art du Livre à l'Imprimerie Nationale. Paris: l'Imprimerie Nationale, 1973. [ see below] Pages 128-141.

This contains the first actual publication of any of the plates on type-making, nearly 300 years after they were engraved: a plate from 1700 engraved by Quineau, "Gravure des poinçons et frappe des matrices" (Plate 3 in {Mosley 1991}, "Making punches") and a plate from 1694 engraved by Simonneau, "Fonderie de caractères" (Plate 5 in {Mosley 1991}, "Casting type.")

{IN 1973} L'art du livre à l'Imprimerie nationale. Paris: l'Imprimerie Nationale, 1973.

This book should not be confused with the entirely different 1951 work of the same name from the same source {IN 1951},

This 1973 book contains two articles of great interest here, Anne Sauvy's "Le Cabinet du Roi" {Sauvy 1973} and André Jammes' "Le Grandjean" {Jammes 1973} .

The first complete publication of the eight plates on type-making was in James Mosley's 1991 article, "Illustrations of Typefounding engraved for the Descriptions des Arts et Métiers of the Académie Royale des Sciences, Paris, 1694 to c. 1700." which appeared in the fine press journal Matrix, No. 11. {Mosley 1991}. He also published a wash drawing related to one of them, and three rough drawings from Truchet's notebooks. Mosley's article remains the definitive treatment of these plates and their context.

{Mosley 1991} Mosley, James. "Illustrations of Typefounding engraved for the Descriptions des Arts et Métiers of the Académie Royale des Sciences, Paris, 1695 to c. 1700." Matrix No. 11 (Winter 1991): 60 - 80.

Portions of five of the plates were reprinted in both editions of Fred Smeijers' book Counterpunch {Smeijers 1996, 2011} . (In the first edition they're hiding in fold-out leaves behind the front and back covers.) But these reprints omit the bottom 2/3 of each of these plates which show detail views of the instruments.

{Smeijers 1996/2011} Smeijers, Fred. Counterpunch: Making Type in the Sixteenth Century[;] Designing Typefaces Now . Ed. Robin Kinross. (London: Hyphen Press, 1996.)

A "revised and reset" edition, lacking Kinross' name, was published by the same press in 2011.

7. Digital Availability of the Second MS (2012, 2013)

I am indebted to James Mosley's footnotes for learning of the digital availability of this manuscript. As I will never tire of saying, one of the most useful things you can do with your time is to take any article by James Mosley and sit down and read its footnotes very carefully. Mosley's work is stunningly good.

As noted above, the manuscript filed in the Bibliothèque Nationale de France as MS 9157 and MS 9158 is a manuscript copy of Jaugeon made, probably, in the 1780s. Jammes says that its text is "less complete" but that it "contains plates which are not in the first manuscript" (p. 72). Mosley says it "introduces some errors, but it appears to be intended as a full transcription of the original text, repeating its mistakes" (p. 8).

Fortunately, this manuscript has been digitized and is now available freely online in the "Gallica" digital library of the BNF.

MS 9157 may be accessed at this Gallica location: http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b9072486r

MS 9158 may be accessed at this Gallica location: http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b90652236

The terms of use of this digital edition from Gallica/BNF do assert their rights over it, but permit use for noncommercial purposes. (All reproductions from it on this page are entirely noncommercial.)

For convenience, therefore, here are local copies of the Gallica/BNF PDF:

Jaugeon, MS 9157

Description et perfection des arts et métiers, des arts de construire les caractères, de graver les poinçons de lettres, de fondre les lettres, d'imprimer les lettres et de relier les livres, par monsieur JAUGEON, de l'Accadémie roale [sic, for royale] des Sciences. Shelfmark: Français 9157. Date d'édition: 1701-1800 [Mosley says "about 1780"]

This is the volume which includes the now infamous "Constructions des Lettres" for the Romain du Roi. See the modern texts by Jammes for a rehabilitation of this work, which has been incorrectly understood and interpreted since the time of Fournier.

Jaugeon, MS 9158 [incl. typefounding]

Description et perfection des arts et métiers, des arts de construire les caractères, de graver les poinçons de lettres, de fondre les lettres, d'imprimer les lettres et de relier les livres, par monsieur JAUGEON, de l'Accadémie roale [sic, for royale] des Sciences. 1704. Shelfmark: Français 9158. Date d'édition : 1701-1800 [Mosley says "about 1780"]

This is the volume with the plates and text of most direct interest to punchcutters and typefounders.

That's the good news. The bad news is that they scanned it at a very low resolution (often only 1024 pixels wide). This means that when you look closely, it's really hard to read. I can't read French myself, but often I will transcribe a text and have a machine translation service (such as Google's) translate it for me. This gives only a rough (and sometimes very funny) translation, but if you know the technical area it can be very useful. Here, I can't even make out the words to do this. I am assured by a friend who is a native French speaker that this digitization is in fact readable, though.

Fortunately, the resolution of this digitization is sufficient for viewing the plates. Since these plates are so very important, and since their publication history has been so troubled, I'll extract them from the PDF and reproduce them here.

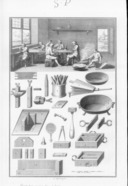

The plates of interest to type-makers appear in two locations in the manuscript: first near the beginning and later, in smaller versions, near the text. The versions here are the ones which appear near the beginning of MS 9158. The titles of the plates used here are those used by Mosley when he reprinted them in Matrix 11 in 1991. For each image below, clicking on the image will bring up the full-resolution (such as it is) PNG-format image. Below each is a link to a PDF conversion of this image; the PDF version may be easier to scale and zoom in on, depending upon your software.

Plate: Preparing Materials and Making Counterpunches. (Mosley's Plate 2)

As a PDF: jaugeon-bnf-ms-fr-9157-9158-plate-m02-preparing-materials-and-making-counterpunches-1054x1463-png.pdf

Plate: [Not titled in Mosley; it is his plate 8. It shows stepped blocks which Mosley thinks are probably physical gauges (rather than abstractions of ideas about size) together with several punchcutter's tools]

As a PDF: jaugeon-bnf-ms-fr-9157-9158-plate-m08-gauges-1024x1494

Plate: Making Punches. (Mosley's Plate 3)

As a PDF: jaugeon-bnf-ms-fr-9157-9158-plate-m03-making-punches-1024x1487-png.pdf

Plate: Making Matrices. (Mosley's Plate 4)

As a PDF: jaugeon-bnf-ms-fr-9157-9158-plate-m04-making-matrices-1024x1496-png.pdf

Plate: Casting Type. (Mosley's Plate 5)

As a PDF: jaugeon-bnf-ms-fr-9157-9158-plate-m05-casting-type-1024x1494-png.pdf

Plate: The Mould. (Mosley's plate 6) This shows a typefounder's hand mold in the French style, employing base plates for mounting the components and the "male and female gauges" ("potences") for aligning the body and carriage when closed.

As a PDF: jaugeon-bnf-ms-fr-9157-9158-plate-m06-the-mould-1024x1493-png.pdf

Plate: Dressing Type. (Mosley's plate 7)

As a PDF: jaugeon-bnf-ms-fr-9157-9158-plate-m07-dressing-type-1024x1448-png.pdf

There follow several plates on fonting schemes or bills, and then the plates showing printing generally.

The section of plates near the beginning of MS 9158 does not include the relatively well-known table of "Calibres de toutes les sorts et grandeurs de Lettres" (which Mosley reprinted as his plate 1). It is included, however, in the body of the text.

As a PDF: jaugeon-bnf-ms-fr-9157-9158-p043-plate-m01-calibres-de-toutes-les-sortes-et-grandeurs-de-lettres-crop-table-680x1024-png.pdf

[TO DO: Try to make out the captions/descriptions for the plates and transcribe and translate them.]

8. Mosley's Translation of the Section on Hand Moulds (2015)

The material in Jaugeon relating to hand molds has been translated into English and published in an excellent paper by James Mosley (once again, slow down and read his footnotes!)

{Mosley 2015} Mosley, James. "Jacques Jaugeon's account of the typefounder's mould, from the text of the 'Description des arts et Métiers', 1704." Journal of the Printing Historical Society. New Series, No. 23 (Autumn 2015): 6 - 43.

This entire issue of the PHS Journal is devoted to various articles by Mosley. It belongs on every typefounder's bookshelf.

{Cole & Watts 1951} Cole, Arthur Harrison and George B. Watts. The Handicrafts of France as Recorded in the Descriptions des Arts et Métiers 1761-1788. Boston: Baker Library of the Harvard Graduate School of Business Administration, 1951.

Originally Publication No. 8 of the Kress Library of Business and Economics. This is now available as a print-on-demand reprint by Literary Licensing LLC (2011-10-15), ISBN-13: 978-1258208363.

{IN 1951} L'art du livre à l'Imprimerie nationale des origines à nos jours. Paris: l'Imprimerie Nationale, 1951.

This book is the catalogue of an exhibition commemorating the history of l'Imprimerie Nationale held at the Galerie Mazarine, 18 April - 31 May, 1951. It should not be confused with the entirely different 1973 work of the same name from the same source, {IN 1973}. This 1951 work is in copyright in the US, but is available digitally through the "Gallica" digital library of the Bibliothèque Nationale de France at: http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k6457299j/f1.image

{IN 1973} L'art du livre à l'Imprimerie nationale. Paris: l'Imprimerie Nationale, 1973.

This book should not be confused with the entirely different 1951 work of the same name from the same source {IN 1951},

This 1973 book contains two articles of great interest here, Anne Sauvy's "Le Cabinet du Roi" {Sauvy 1973} and André Jammes' "Le Grandjean" {Jammes 1973} .

{Jammes 1961} Jammes, André. La Réforme de la typographie royale sous Louis XIV: Le Grandjean. Paris: Libraire Paul Jammes, 1961.

The first edition of this work was printed by l'Imprimerie nationale for Libraire Paul Jammes (Paris, 1961) with pulls from the original copper plates.

Reprinted, at reduced size, by Editions Promodis in 1985.

In his 2015 translation of the portion of Jaugeon on hand molds, Mosley says that this 1961 work by Jammes "remains the fundamental study." {Mosley 2015}, p. 7. The practical type-maker should note, however, that the plates in it include only those relevant to the Romain du Roi. None of the plates of punchcutter's or typefounder's equipment are reproduced.

{Jammes 1963} Jammes, André. "Louis XIV, sa Bibliothèque et le Cabinet du Roi." The Library. Fifth Series, Vol. 20, No. 1 (March 1965): 1-12.

The journal The Library is the Transactions of the Bibliographical Society of Oxford. This is a paper "Read before the Bibliographic Society on 17 December 1963." Not illustrated.

{Jammes 1965} Jammes, André, trans Gillian Riley. "Académisme et Typographie: The Making of the Romain du Roi." Journal of the Printing Historical Society. No. 1 [original series] (1965): 71-95.

It is worth quoting in full the final paragraph of this article by Jammes (in translation, by Riley) for a better understanding both of the nature of the Romain du Roi and of the work of Jaugeon and the Bignon committee:

"The romain du roi is not the result of a compromise between the common sense of a craftsman [Granjean] and the unpractical theorizing of official scholars. A matter so important as the creation of a royal type could not possibly be left to chance in the century of the académies. The romain du roi, reflection of the splendor of the reign of Louis XIV, is the result of the continuous collaboration between scholars, men of letters, bibliographers, and artsists, the result of much guessing and some practical experiment, the synthesis of the tastes of one period with an earlier tradition whose diverse aspects had been scrupulously investigated and studied."

{Mosley 2002} Mosley, James, et. al. Le Romain du Roi: la typogrpahie au service de l'État, 1702-2002. Lyon, FR: Musée de l'imprimerie de Lyon, 2002.

Several of the plates from Jaugeon are reprinted, including the "Calibres," the plates on the mold and on typefounding, and the watercolor of a typefoundry previously published by Mosley in Matrix 11. It also reprints several examples of the original use of the Romain du Roi for a volume illustrating medals commemorating the achievements of Louis XIV. It is easy for us today to think of the "Romain du Roi" as if it were a typeface published in a specimen book, but this was not the case at all.

{Mosley 2007} Mosley, James. [Untitled posting in a thread] "Romain du Roi revival." Typophile online forum. Thread start 2006-08-01 by Bram Pitoyo. Mosley posting 2007-01-20. Online at: http://www.typophile.com/node/27378#comment-179175

{Mosley 2015} Mosley, James. "Jacques Jaugeon's account of the typefounder's mould, from the text of the 'Description des arts et Métiers', 1704." Journal of the Printing Historical Society. New Series, No. 23 (Autumn 2015): 6 - 43.

{Sauvy 1973} Sauvy, Anne. "Le Cabinet du Roi et les projets encyclopédiques de Colbert." [a chapter in] L'Art du Livre à l'Imprimerie Nationale. Paris: l'Imprimerie Nationale, 1973. Pages 102-127.

{Smeijers 1996/2011} Smeijers, Fred. Counterpunch: Making Type in the Sixteenth Century[;] Designing Typefaces Now . Ed. Robin Kinross. (London: Hyphen Press, 1996.)

A "revised and reset" edition, lacking Kinross' name, was published by the same press in 2011.

All portions of this document not noted otherwise are Copyright © 2017 by David M. MacMillan and Rollande Krandall.

Circuitous Root is a Registered Trademark of David M. MacMillan and Rollande Krandall.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons "Attribution - ShareAlike" license. See http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/ for its terms.

Presented originally by Circuitous Root®