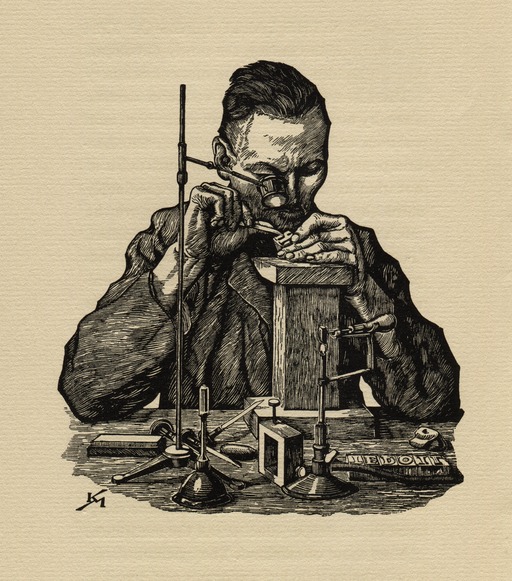

This is a woodcut by Karl Mahr as published in the Bauer Type Foundry book Human Touch. (NY: The Spiral Press, 1937). This engraving appeared originally in Der Druckbuchstabe: Sein Werdegang in der Schriftgießerei dargestellt in Holzschnitten und Versen . ([no location, but Mahr in Frankfurt a. M.]: Verein Deutscher Schriftgießereien E.D., 1928). Go up one level for a discussion of this work as a whole, and for general works on type-making.

The image above is a reduced-scale version of the original scan. It is 2048 pixels wide, and quite enough for most purposes. Here is a full-resolution version (80 Megabytes): bauer-human-touch-1937-1200rgb-hand-punchcutter-crop-6700x7600.png

I am indebted to the scholar and punchcutter Stan Nelson for his gracious assistance in helping me to understand both this illustration as a whole and the individual tools shown in it. He also directed me to several important original sources. All of the mistakes which remain, both of fact and of interpretation, are my own.

This illustration repays careful study for two reasons: first because of what is shown in it, and second because it is not necessarily what it appears to be.

To take the second issue first: What is the profession of this man and what is it that he is doing? The answer would seem to be easy - he is a punchcutter. In the German text of the original, he is referred to as "der Stempelschneider," and that translates literally enough as punch cutter. In his English translation of the original Mahr work, Printing Types: Their Birth in the Typefoundry Depicted in Woodcut and Verse by Karl Mahr (Terra Alta, WV: The Hill and Dale Private Press and Typefoundry, 2000)) the American typefounder and matrix maker Paul Hayden Duensing titles this illustration "The Hand-Punch-Cutter." So it is almost certain that this man would have listed "punchcutter" as his occupation - yet he is not cutting a punch.

What he is doing is cutting a "patrix" (though he might not have called it that) or pattern type. He is cutting it not in steel, but in typemetal (a lead alloy). Such a patrix would then be used in an electroforming operation to produce a matrix.

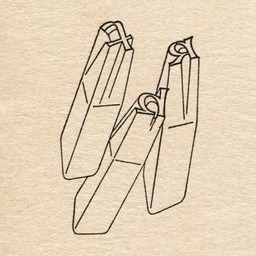

Traditional punches are relatively long in comparison to their cross section. The image below left shows three punches of traditional form (from R. Hunter Middleton's An Essay on the Forgotten Art of the Punchcutter (1965)) Compare these with the patrices shown in Mahr's woodcut, below right, which are nearly cubes.

It is true that in the 20th century punches of a form similar to these patrices were used (e.g. by The Monotype Corporation Ltd., as shown in their 1956 film Type Faces in the Making), but the presence in this illustration of one tool unique to patrix engraving in typemetal (a soldering iron) indicates that the object being engraved is a lead-alloy patrix, not a steel punch.

Very broadly speaking, there are three methods for producing typefounders' matrices: punchcutting, patrix engraving, and direct matrix engraving. The problem is that most accounts of matrix making, in English at least, either date from or trace their origins to accounts written in the early 20th century. This was a period in which the pantographic rotary engraving machine had swept older methods of hand work from the field, and in doing so had generated considerable controversy.

Now, pantographs can be (and were) used for all three of these methods. Indeed, Linn Boyd Benton developed his pantograph for the second of them, patrix engraving, though it became famous for its use in the other two methods. But the popular accounts written concentrated either on the use of pantographs for engraving punches (e.g., for Monotype by Beatrice Warde) or for directly engraving matrices (e.g., at American Type Founders, or by Goudy). The method of pantographic engraving of patrices for use in electroforming matrices was ignored as if it didn't exist (even though, for example, it was how almost all Lanston Monotype display matrices were made - and it was therefore the dominant method in America for creating display type in the 20th century).

At the same time, a backlash in the world of fine printing set in and there was a resurgence in traditional hand punchcutting. This was a good thing in itself, but the accounts written by punchcutters such as Paul Koch emphasized very traditional methods of hand engraving punches for driven matrices. The hand engraving of patrices, which was extremely important in the production of display types in the 19th century, was completely ignored.

Of course, the status of the method of patrix engraving wasn't helped in the least by the fact that the second part of this process - electroforming - was responsible for the widespread pirating of types in the 19th century. Most American typefoundries preferred to say very little about it.

Outside the Anglophone world, however, accounts seem to have been more balanced. In Mahr's original text, for example, he says (in Duensing's translation):

"He [der Stempelschneider] forms with graver, many things, In hardened steel and soft lead."

So it would seem that the term "stempelschneider" referred not strictly to a punch cutter (in steel) but also to patrix cutters (in lead).

The Bauer foundry was quite forthright about the method of patrix engraving. In the book in which this engraving appears, Human Touch, they put all three methods on equal footing. Of the patrix engraving method, they say:

"Another method employs electrotyping. The type-cutter engraves the letter in the polished surface of a lead block, and from this original a negative form, usually of nickel, is made by the galvanic process. After finishing, this form is fitted into a zinc block which serves as the matrix."

In a more comprehensive volume, Wie eine Buchdruckschrift entsteht. (Frankfurt am Main: Bauersche Giesserei, n.d. [1933? and also 1953?]) Konrad F. Bauer illustrates all three methods in parallel (paying particular attention to the electroforming process).

At some point near this period, the Klingspor foundry put out a series of posters showing these processes, including electroforming .

Much later, two volumes which documented processes near the end of the Stempel foundry illustrated patrix engraving: Ronald Schmets' Vom Schriftgießen: Porträt der Firma D. Stempel, Frankfurt am Main. (Darmstadt: Technische Hochschule Darmstadt, 1987). and Walter Wilkes' Das Schriftgießen: Von Stempelschnitt, Matrizenfertigung und Letterguss: eine Dokumentation von Walter Wilkes . (Stuttgart: Technische Hochschule Darmstadt, 1990.) The Wilkes book shows August Rosenberger (famous for cutting, inter alia, the plates from which Zapf's book Pen and Graver were printed) at work engraving patrices.

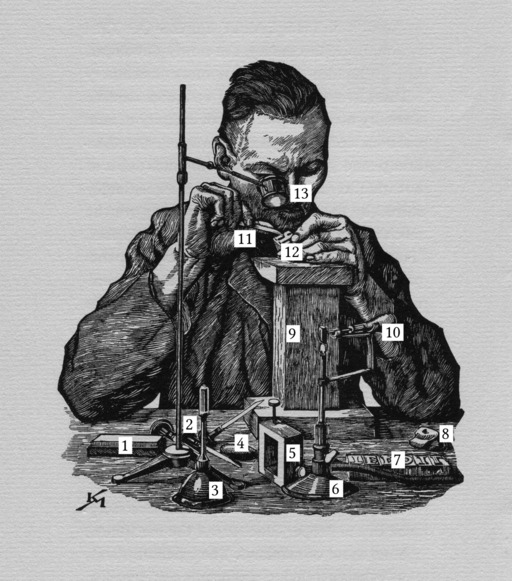

Many of the tools used by der Stempelschneider in engraving patrices would be the same as those used in engraving punches, but some of the tools differ. Below is an annotated version identifying the tools shown in this illustration.

1. An oilstone for use in sharpening gravers. (Oilstones were sometimes also used for surfacing steel punches, but the size of this oilstone indicates that it would have been used for sharpening.)

3. This is probably a small oil lamp, the flame of which is used to blacken the patrix in the process of taking a smoke proof. The candle was the more traditional tool, but an oil lamp would work.

4. The handle of a tool which is obscured. It might be another graver, though it is the wrong sort of handle for that. It might be a file.

5. This is a tool used to hold a punch or patrix square when taking a smoke proof of it. We have not yet ascertained its proper name. This frame is type high.

Stan Nelson notes that this tool is not the superficially similar "screw stock" shown in Paul Koch's essay "The Making of Printing Types" in The Dolphin, No. 1 (NY: The Limited Editions Club, 1933) on pages 31-32. (Koch used his screw stock for to hold the punch squarely when transferring the design to it, not for making smoke proofs.)

Neither is this a facing tool or "facer" (see Carter's edition of Fournier or Williams Engineering Co., Ltd. Type Founders' Equipment catalog (1919) (where it is called a "jointer."))

6. A specialize form of Bunsen burner; see also item #10, below.

7. Patrices which have been engraved. Note that the 'L' is wrong-reading (which is correct); patrices, types, and punches are all wrong-reading, while matrices and print are right-reading.

8. It is not clear what this tool is. Stan Nelson thinks that it might be either (a) a piece of plasticene clay used to coat the patrix or punch with an oily film so as to help it retain the soot impression of a design transferred to it, or (b) a piece of clay used to clean pick up the small metal chips produced by the engraving. He suspects it is the latter.

9. A "pin." A conventional jeweler's "bench pin" is simply a piece of wood projecting from the workbench surface which generally has a notch in its end. It is a useful work-bracing device when filing, sawing, etc. The punchcutter's "pin" is essentially the same device raised on a stand for close work. Fournier does not show the pin, but it is shown, for example, in photographs of the German punchcutter Rudolf Koch at work.

10. This is clearly some form of soldering iron. Since the process of patrix engraving is so poorly documented, I do not yet know its exact purpose here. A gas-heated soldering iron of this form would be sufficient to melt typemetal. Here is a detail view of it:

Stan Nelson further notes that the position of the person here, with elbows resting on the bench, is natural and convenient for the use of the graver at an elevated pin such as this. When using the file, the punchcutter would not rest his or her elbows on the bench.

Bauer, Konrad F. Wie eine Buchdruckschrift entsteht. (Frankfurt am Main: Bauersche Giesserei, n.d. [1933? and also 1953?])

Carter, Harry. Fournier on Typefounding: The Text of the Manuel Typographique (London: The Soncino Press, 1930).

Reprinted twice: (NY: Burt Franklin, 1973), with new introduction by Carter, and (Darmstadt: Technische Hochschule Darmstadt, 1985), with introduction and notes by James Mosley. See also digital versions of the original editions, mirrored in these Notebooks .

Cinamon, Gerald. Rudolf Koch: Letterer, Type Designer, Teacher. New Castle, DE / London: Oak Knoll Press / The British Library, 2000.

This article is available online at Carnegie-Mellon University's Posner Library: http://posner.library.cmu.edu/Posner/

Mahr, Karl. Der Druckbuchstabe: Sein Werdegang in der Schriftgießerei dargestellt in Holzschnitten und Versen . ([no location, but Mahr in Frankfurt a. M.]: Verein Deutscher Schriftgießereien E.D., 1928).

Mahr, Karl. Trans. Paul Hayden Duensing. Printing Types: Their Birth in the Typefoundry Depicted in Woodcut and Verse by Karl Mahr . (Terra Alta, WV: The Hill and Dale Private Press and Typefoundry, 2000)).

Middleton, R. Hunter. An Essay on the Forgotten Art of the Punchcutter. (1965)

The Monotype Corporation Ltd. "Making Sure" At the Monotype Works: Type Faces in the Making (Salfords, UK: The Monotype Corporation Ltd., 1956)

Nelson, Stan. [personal communications]

Schmets, Ronald. Vom Schriftgießen: Porträt der Firma D. Stempel, Frankfurt am Main. (Darmstadt: Technische Hochschule Darmstadt, 1987).

Smeijers, Fred. Counterpunch. London: Hyphen Press, 1996.

This article is available online at Carnegie-Mellon University's Posner Library: http://posner.library.cmu.edu/Posner/

Wilkes, Walter. Das Schriftgießen: Von Stempelschnitt, Matrizenfertigung und Letterguss: eine Dokumentation von Walter Wilkes . (Stuttgart: Technische Hochschule Darmstadt, 1990.)

The original printed version of this woodcut, from Human Touch (NY: Bauer Type Foundry / Spiral Press, 1937) is in the public domain due to the failure of this volume to comply with copyright formalities, as then required, upon publication. The various versions of it reprinted here remain in the public domain.

All portions of this document not noted otherwise are Copyright © 2012 by David M. MacMillan and Rollande Krandall.

Circuitous Root is a Registered Trademark of David M. MacMillan and Rollande Krandall.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons "Attribution - ShareAlike" license. See http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/ for its terms.

Presented originally by Circuitous Root®

Select Resolution: 0 [other resolutions temporarily disabled due to lack of disk space]