The use of a Hand Scraper may be undertaken for two logically distinct purposes.

"Hand Scraping" proper is the process of using a scraper held in the hands to remove small amounts of metal from a precision surface so as to provide an accurate bearing surface to within some tolerance. (The scraper itself may be either manual or powered; the use of a power scraper is still hand scraping because the tool is held in and controlled by the hands.) This kind of hand scraping is the way in which the finest machine slideways have been produced from the early 19th century to the present. The finish it produces may be attractive in its own way, but it is functional process, not a decorative one. For more on this type of hand scraping, see the Hand Scraping Notebook.

Hand scraping may also be done to produce a decorative finish on a surface. This is the topic of this present Notebook.

Some controversy exists as to whether or not this decorative finish might also perform a useful function when it is used between moving parts (as opposed to merely decorating a surface). Some hold that it provides minute reservoirs for oil and thus aids in lubrication and/or that by breaking up the surface it reduces "stick-slip" between moving parts such as machine slideways. Others hold that it provides minute reservoirs for retaining abrasive grit and is therefore undesirable as it speeds wear. I know of no methodical research which has confirmed or denied either position; it remains a matter of anecdote and opinion.

These hand scraped finishes have an appearance which is distinguishable from functional hand scraping. The real distinction, though, is that functional hand scraping is done in an iterative process of constant comparison to references and correction based on those comparisons, while decorative hand scraping is not. The various distinctive patterns produced by decorative hand scraping include "Frosting" and "Flaking."

Note that the term "Frosting" as used here (and in the machine trades) is distinct from both the "Dead White" or "Frosted" finish employed by horologists and described by Saunier and from the acid "Frosting" employed as a preparatory stage for the guilding of clock parts.

To further confuse matters, Frosting and Flaking have at times been called "Spotting" in reputable sources (e.g., Machinery's Encyclopedia, Vol. 5 (1917)) even though they are cutting processes unrelated to the well-established abrasive process of Spotting.

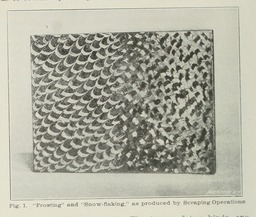

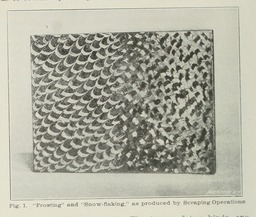

Here is Fairfield's illustration of "frosting" (on the left) and "snow-flaking" (on the right).

Of frosting, Fairfield says that it "is accomplished by giving the scraping tool a pecuilar 'wiggle,' as the cut is made; this is not easy to do, and difficult to describe. However, if well done, it leaves a very handsome finish." (p. 474)

H. L. Wheeler, in "How to Scrape Metal Surfaces," Popular Science, Vol. 105, No. 3 (Sept. 1924): 84, 86, 88, (viewable online via Google Books) illustrates three different patterns of "frosting": "crescent," "diagonal diamond," and "straight diamond."

See Connelly, Machine Tool Reconditioning , p. 171.

Fairfield describes flaking (he call is "snow-flaking") thus: "The scraping tool is pushed squarely ahead to give spots of an established size and at established intervals. Similar spots are then made to fill the intervening spaces, using the scraper at right angles to the previous direction of motion or push." (p. 474)

See also "Aluminum Flaking on Bugatti Automobiles" , below.

This is not really a flaking (or even hand scraping) method at all. It is the term Connelly, in Machine Tool Reconditioning (pp. 173-174) applies to the abrasive spotting technique.

Apparently the traditional manner of finishing the engine surfaces (especially the cam covers) of Bugatti automobiles is by hand scraping (more specifically (I'm pretty sure) in a flaking pattern). This is an interesting application (from the point of view of a machinist) because it involves scraping a soft metal, aluminum, rather than cast iron or steel.

(If you are a Bugatti enthusiast who came directly to this section via an Internet search, rest assured that "aluminum flaking" has nothing to do with the deterioration of metal! Rather, the particular pattern of purely decorative "hand scraping" which, to judge from the illustrations and accounts I've seen, appears to be preferred for finishing Bugatti engines is a pattern known in the machine trades as "flaking" or (earlier) "snow-flaking.")

Here are two examples of flaking as applied to Bugatti engines. The one on the left is of a 1938 Bugatti Type 57SC Atlantic Coupe. The one on the right is of a 1937 Bugatti Type 37A. However, both images present an interesting potential source of confusion. (See the Notebook on Engine Turning vs. Spotting for more on the potential confusion of terminology when looking at Bugatti engine compartments.) Briefly, the engines in the two photos here are flaked (hand scraped), but the firewalls are spotted ( not "engine turned.")

(Both images are from Wikimedia Commons. The one of the Type 57SC is by user Sfoskett and is of a vehicle in the Ralph Lauren collection on display at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts in 2005. License: GFDL or CC By-SA 3.0 Unported. Location: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:RL_1938_Bugatti_57SC_Atlantic_engine.jpg. The one of the Type 37A is by user Liftarn and is of a vehicle at the Prins Bertil Memorial in Stockholm, Sweden. License: GFDL or CC By-SA 3.0 Unported. Location: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bugattiengine.JPG

1924 Grand Prix Bugatti Type 35 Lyons

Giddings, Peter. "1924 Grand Prix Bugatti Type 35 Lyons." This is a web page with an illustrated description of this particular automobile. http://petergiddings.com/Cars/lyons_bugatti.html It contains several photographs, in black and white, which show both the hand scraping (flaking) of the engine and the frosting of the firewall.

1911. Fairfield. Machinery.

Fairfield, H. P. "Hand Scraping." In the "Machine Shop Practices" column of Machinery, 1911. (The icon here links "up and over" to a presentation of this material in the "regular" Hand Scraping Notebook.)

Fairfield's article is particularly useful because it provides a contemporary (1911) illustration of what was thought of as "frosting" and flaking (or "snow-flaking" as he calls it). He is suspicious of the use of these techniques "to deceive the uninitiated, who are apt to consider it as proof of previous careful fitting." He writes of these techniques as entirely decorative, and makes no mention of any use for them in lubrication or reduction of "stick-slip."Here is Fairfield's illustration of "frosting" (on the left) and "snow-flaking" (on the right).

1924. Wheeler. Popular Science.

Wheeler, H. L. "How to Scrape Metal Surfaces." Popular Science, Vol. 105, No. 3 (Sept. 1924): 84, 86, 88. Viewable online via Google Books.

While this article is good in its own way, it tries to cover the entire field in a couple of pages (including regular hand scraping, bearing scraping, and frosting). It is of particular interest, though, because (a) it shows an unusual method of sharpening the hand scraper which involve a diagonal cutting surface on the end of the blade (of a scraper with a convex cross-section), and (b) it shows three patterns for frosting: "crescent," "diagonal diamond," and "straight diamond."

1955. Connelly. Machine Tool Reconditioning

Connelly, Edward F. Machine Tool Reconditioning. (St. Paul, MN: Machine Tool Publications, 1955). Connelly's book remains the standard comprehensive volume on using functional hand scraping to rebuild machine tools. He does, however, devote a chapter to decorative hand scraping. He is of the opinion that these techniques do assist in lubrication (pp. 165 and 172).

The methods he describes are frosting (where he discusses in some detail the sharpening of the scraper for frosting, the stance to be used when frosting, and the marks produced by frosting), butterfly frosting (illustrated with a photograph), and flaking. He speaks derisively of spotting (though he calls it "circular flaking").

Of the distinctions between techniques, he says: "There is very little similarity between flaking and frosting. The designs generated by each process are different, as well as the techniques employed in producing them." But he cautions that "among some operators the expressions are used interchangeably" and that "others erroneously confuse the techniques by giving the name of one to the other". Connelly worked very precisely, both in words and in metal.

Phillips & Leydon on Bugatti Hand Scraping

As noted in the "Patterns" section above, apparently the traditional manner of finishing the engine surfaces (especially the cam covers) of Bugatti automobiles is by hand scraping (flaking, I'm pretty sure). This is an interesting application (from the point of view of a machinist) because it involves scraping a soft metal, aluminum, rather than cast iron or steel.

An article on this by Overton Axton ("Bunny") Phillips appeared in the Vol. 12, No. 2 (circa 1973; I'm not sure of the exact date) issue of Pur Sang, the journal of the Bugatti Club of America. This was reprinted in Bugantics, the journal of The Bugatti Owners' Club (I don't know the bibliographic information for this reprinted version). It is very brief, but essential reading if you plan to do decorative Flaking (especially of Bugattis). He outlines his technique, and discusses which Bugattis were finished by Flaking, which parts of a Bugatti might be finished in this way, and which parts of a Bugatti may and may not be finished by Spotting (he calls it "engine turning," which it isn't, really).

A followup article by Christopher Leydon, "Bugatti Hand Scraping," appeared in Pur Sang Vol. 32, No. 2 (Spring 1992). This article is online in two locations: On Leydon's own website, at http://christopherleydon.com/Zwords/92PurSang/92pursang.html and in The Bugatti Review, Vol. 9, No. 2 at http://www.bugattirevue.com/revue23/scrape.htm. The latter presentation contains an additional color photograph by the editor, Jaap Horst, of a hand scraped Bugatti engine.

All portions of this document not noted otherwise are Copyright © 2012 by David M. MacMillan and Rollande Krandall.

Circuitous Root is a Registered Trademark of David M. MacMillan and Rollande Krandall.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons "Attribution - ShareAlike" license. See http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/ for its terms.

Presented originally by Circuitous Root®

Select Resolution: 0 [other resolutions temporarily disabled due to lack of disk space]